Exhibit of the month

Work first then play

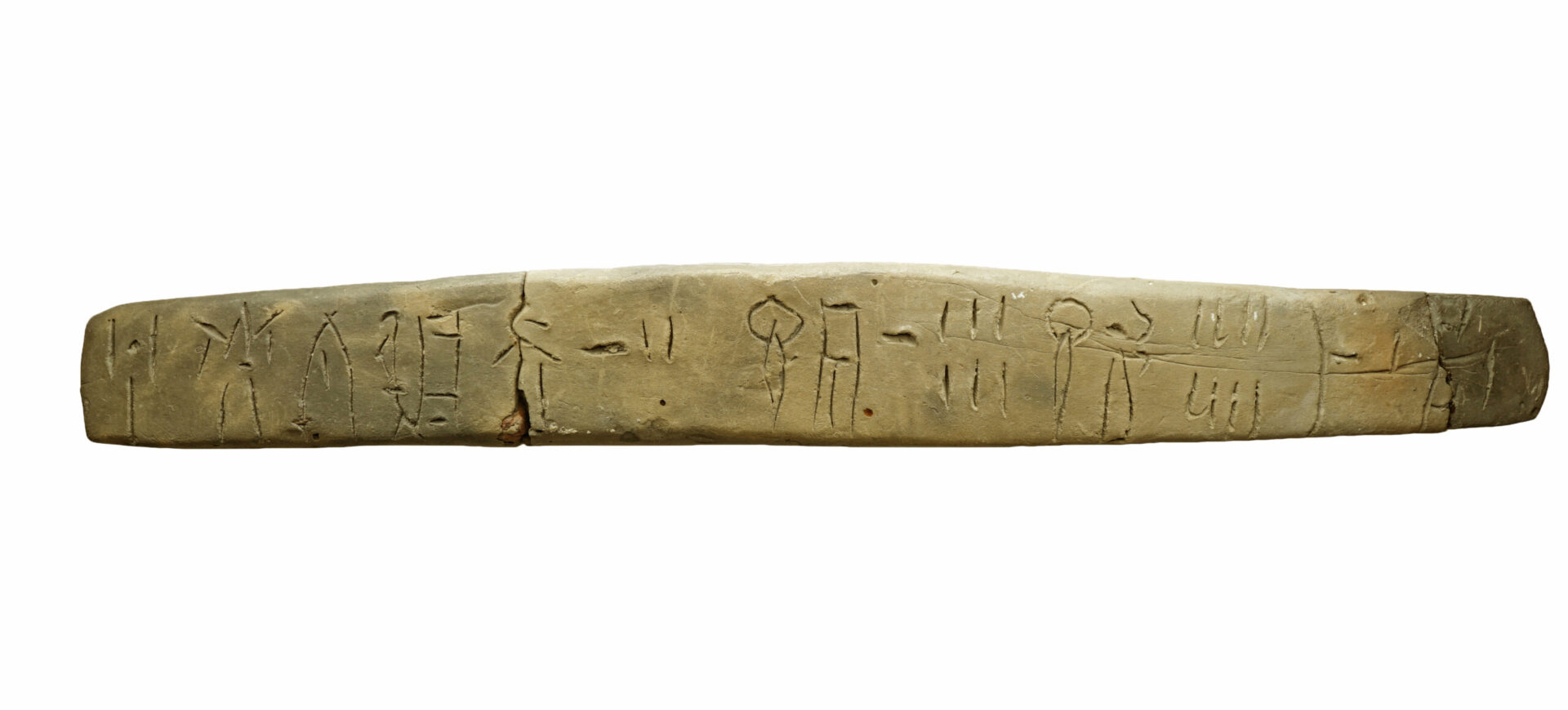

Linear B Tablet recording personnel

National Archaeological Museum

Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities, inv.no. P 12572 (PY Aa 85)

Provenance: Pylos, Palace of Ano Eglianos (“Palace of Nestor”).

Dimensions: Length: 22.1 cm, Width: 2.6 cm, Thickness: 1.8 cm.

Chronology: 13th c. B.C.

Display Place: Gallery 4, Showcase M 29 (no. 1)

The Linear B tablet with the short inscription preserves valuable information about child labor in the Mycenaean palace of Pylos. Sixteen girls (κόραι) and 8 boys (κούροι) are recorded along with a group of 12 women working as weavers[1] and two supervisors of the group’s work.[2]

More than 600 children, girls and boys are part of the palace workforce in Pylos and are always recorded with groups of adult personnel. When the record includes children of both sexes, as is the case in this particular tablet, then the children are accompanied by groups of women workers.[3] These women seem to be their mothers who are obliged to work while taking care of their offspring.[4] At the same time, children are being instructed in their mothers’ craft, thus participating in the division of labor and earning their own living. Apart from the names of the children, their ages also escape us,[5] although it has been argued that participation in the work at the palace would have involved children from 6 years old to teenagers. The analysis of palm prints on tablets from the palace of Knossos has resulted to the identification of 8 to 12 years old children’ impressions leading to the conclusion that they were involved in preparing the tablets so that they would be ready for use by the scribes (who were probably their fathers).

The children recorded in the Linear B tablets as part of the dependent personnel of the palace who were allocated rations as wages appear to be unrelated to the depictions of children in the Mycenaean art. In the iconography are depicted children who belong to higher social class who are not forced to earn a living[6] thus having plenty of time to play and to participate in rituals and social or sporting events.

Therefore, it seems that social status also determined the way each child spent their time in the Mycenaean palace. As childhood is inextricably linked to the carelessness of play, it seems reasonable to expect that children recorded in the Linear B tablets would also find some time to play. But for these children there was definitely one condition: work first, then play!

[1] The term a-ke-ti-ri-ja (ἀσκήτριαι) probably refers to a specialized occupational term involved in the final processing or decoration of textiles. The term is also attested in Knossos, Mycenae and Thebes.

[2] The acrophonic abbreviations DA (da-ma /damar/) και ΤΑ (*ta-mi-ja /tamija/) refer to supervisors of the work groups. They are paid an increased amount of rations compared to the members of the work group.

[3] When children are recorded with male workers, then these children are always older boys, identified with the term ko-wo followed by the logogram for the man (VIR). It seems that taking care of the younger children was therefore a woman’s responsibility.

[4] It is interesting, however, that the term mother (ma-te) which is mentioned on a Pylos tablet, is not used in the case of these groups of women and their children

[5] On the Knossos tablets the children are additionally identified with the terms me-zo (μείζων, older) and me-wi-jo (μείων, younger). But it is possible that these adjectives refer to various stages of occupational training and not to age. The terms are also recorded in Pylos, where they do not refer to children but objects (e.g. parts of armour or furniture.

[6] Indicative of the high social status as well as the role of children during the practice of worship is the finding of Tomb III from Grave Circle A at Mycenae, where the child who had been buried with the “Priestess” was completely covered with gold plates.

Dr. Katerina Voutsa

Bibliography

Aamodt, Ch. 2012. The Participation of Children in Mycenaean Cult. Childhood in the Past: An International Journal 5.1., 35-50.

Gallou, Ch. 2010. Children at Work in Mycenaean Greece (c. 1680–1050 BCE): A Brief Survey. Childhood and Violence in the Western Tradition, Brockliss, Laurence and Heather Montgomery, eds. Childhood in the Past Monograph Series 1, Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books, 162-171.

Kaczmarek, B., Mycenaean childhood: Linear B script set against archeological artefacts, in Rebay-Salisbury, K. and Pany-Kucera, D. (eds.), Ages and Abilities: The Stages of Childhood and their Social Recognition in Prehistoric Europe and Beyond, Oxford 2020: 122-132

Nosch, M.-L. 2001. Kinderarbeit in der mykenischen Palastzeit, in Akten des 8.Österreichischen Archäologentages am Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Wien (vom 23. bis 25. April 1999). Vienna: Phoibos, 37-43.

Olsen, A. 2014. Women in Mycenaean Greece: The Linear B tablets from Pylos and Knossos,. London and New York: Routledge. (ebook).

Rutter, J. B. 2003. Children in Aegean Prehistory, in Neils, J. and Oakley, J. (eds) Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven: Yale University Press, 30-57.

Sjoquist K.-E. and P. Aström. 1991. Knossos: Keepers and Kneaders (Goteborg: Paul Astroms Forlag).