Exhibit of the month

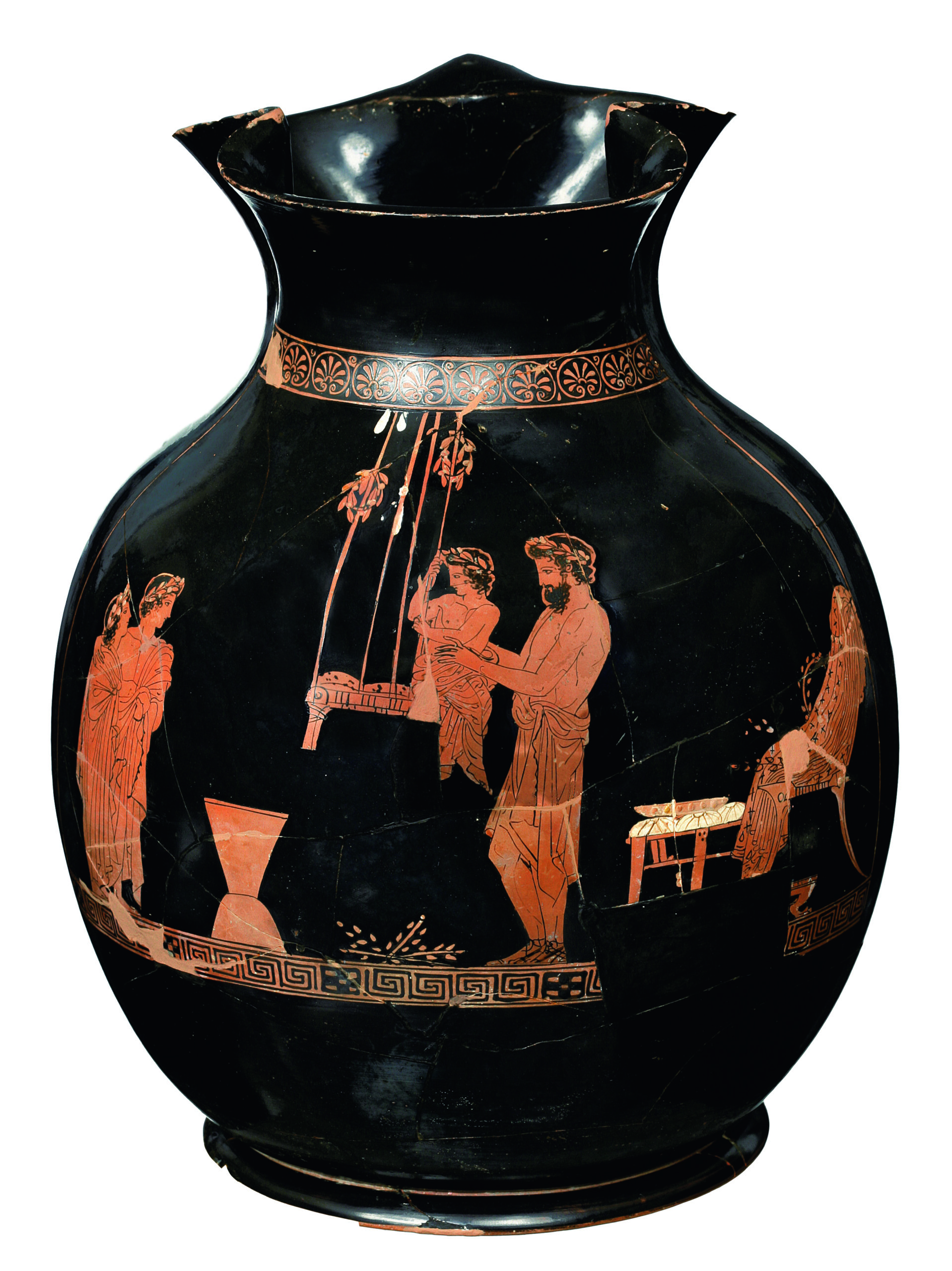

A child on the aiora

Attic red-figure chous

Attributed to the Eretria Painter

National Archaeological Museum

Vase Collection, inv. no. ΒΣ 319

Provenance: Probably from Koropi (Attica)

Dimensions: Ht. 0.22 m.

Date: 430-425 B.C.

On view: Room 61, Showcase 13.

The vase features a scene associated with the Aiōra (Swing) ritual, which probably took place in Attica during the Anthesteria festival [1].

In the centre of the scene hangs a swing (aiōra), on which a crowned bearded man has placed a boy, also crowned. On the ground beneath the swing feature branches and next to them the upper part of a half-buried pithos. To the left stand two older children, whereas to the right lies a klismos (seat with backrest) and a footstool. The chair has been covered with a chiton and himation, adorned with a necklace, a wreath and branches, as if it were a human. In front of the klismos lies a low table with a phiale and three popana (cakes).

According to the prevailing view, the Aiōra ritual is connected with the myth of Erigone, daughter of Icarius, after whom the respective deme of Attica was named. Icarius had been initiated by the god Dionysos himself into the art of wine making; nevertheless, he met his death at the hands of his compatriots who, not having experienced the consequences of drinking, thought he had poisoned them. Erigone, unable to cope with the loss of her father, hanged herself from a tree [2]. The people of Attica, in order to save themselves from Dionysos’ wrath, which caused an epidemic of suicides by hanging among young girls, asked for an oracular statement from the Oracle of Delphi, according to which they would be atoned only if they honoured Dionysos, Icarius and Erigone. They thus instituted the festival of Aiōra, during which the girls were swinging on a swing [3], singing a song called alētis (the wanderer) [4].

A small number of Attic vase-paintings representing young girls swinging attests to the celebration of the ritual in Attica [5]. On the chous by the Eretria painter, the girl has been replaced by a boy, a fact that may echo another version of the myth, where there was no distinction between the sexes of the children participating in the ceremony.

The dressed in garments klismos with the low table in front of it, associates the representation with a theoxeny scene, in which the honoured god or hero, perhaps in this case Erigone [6] herself, has been invited to attend the ceremony and taste the wine and the food-offerings.

The Dionysian festival of Anthesteria is associated with rites of passage that initiate the children into the adult world. One of these was the first tasting of wine by little boys, distributed to them in small choes decorated with scenes from the children’s world, such as those on display in Room 56 of the National Archaeological Museum.

[1] The Anthesteria was a composite three-day Dionysian festival, celebrated at the beginning of spring, during the month of Anthesterion. It was mainly a wine festival and a happy occasion for excessive drinking. The first day was known as the Pithoigia (Jar-opening), on which the pithoi (storage jars) were opened and the new wine was tasted. On the second day, called Choes (Beakers), ceremonies took place at the ancient sanctuary of Dionysus en Limnais (in the Marshes) and probably a procession featuring the ship-cart of Dionysos, known from vase paintings. A wine competition was also held on the same day. The last day, Chytroi (Pots), was dedicated to the dead and included an offering of panspermia (boiled mixed seeds) to Hermes Chthonios. Callimachus mentions the custom of Aiōra along with the Pithoigia and the Choes, but it is not certain which day of the Anthesteria was celebrated.

[2] Another version of the myth (Apollodorus, Epitome, 6.25, 28; scholium in Euripides’ Orestis, 1648) holds that Erigone was the daughter of Aegisthus and Clytemnestra, and half-sister of Orestes. After the murder of her parents, she followed Orestes to Athens seeking his punishment, only to commit suicide after his acquittal.

[3] The association of the myth with the ritual of Aiōra and its interpretation has caused much debate among scholars. Earlier researchers argued that it is a ritual of agricultural magic related to the phases of viticulture, as it coincides with the pruning season. The same myth, according to another view, must have been related to an agos (miasma, pollution) that had to be removed through the ceremony of the Aiōra, before the rebirth of nature in spring. Modern scholars associated Aiōra with the consecration of the new wine, whereas others contended that the innocent playing on the swing replaces semiotically the gloomy swinging on the noose, thus warding off death and ensuring the continuation of life.

[4] Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 14, 10, 19. Lexicographic sources claim that the word alētis was the actual name of the Aiōra ritual (Hesychius, s.v. Ἀλῆτις) but also an Erigone’s epithet, since she has been wandered around looking for her father (Etymologicum Magnum, s.v. Ἀλῆτις).

[5] The theme is also depicted on some South Italian red-figure vases; however, no written evidence confirms that the ritual was actually taking place in Southern Italy.

[6] Some scholars have associated the dressed klismos with Dionysos himself or even with Basilinna, the wife of the archon Basileus, who played an active role in the rituals of the Anthesteria festival, the most important of which was the Hieros Gamos (Sacred Marriage) with Dionysos.

Dr. Maria Tolia-Christakou

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- L. Deubner, Attische Feste (Berlin 1932) 118-121.

- B. C. Dietrich, A Rite of Swinging during the Anthesteria, Hermes 89, 1961, 36-50.

- R. Martin – H. Metzger, Η θρησκεία των αρχαίων Ελλήνων (Αθήνα 1992) 145-148.

- Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum (ThesCRA), VI, 1 (2011) 36-38 λ. Aiora (Α. Kossatz-Deissmann).

- M. Tiverios, Theoxenia of Erigone (?), στο: P. Bádenas de la Peña – P. Cabrera Bonet – M. Moreno Conde – A. Ruiz Rodríguez – C. Sánchez Fernández – T. Tortosa Rocamora (επιμ.), Homenaje a Ricardo Olmos. Per speculum in aenigmate. Miradas sobre la Antigüedad (Madrid 2014) 147-154.

- A. Heinemann, Der Gott des Gelages (Berlin/Boston 2016) 435-442.

- V. Sabetai, Playing at the Festival: Aiora, a Swing Ritual, στο: V. Dasen – M. Vespa (επιμ.), Play and Games in Classical Antiquity. Definition, Transmission, Reception (Liège 2021) 61-77.