Exhibit of the month

Dangerous bull games

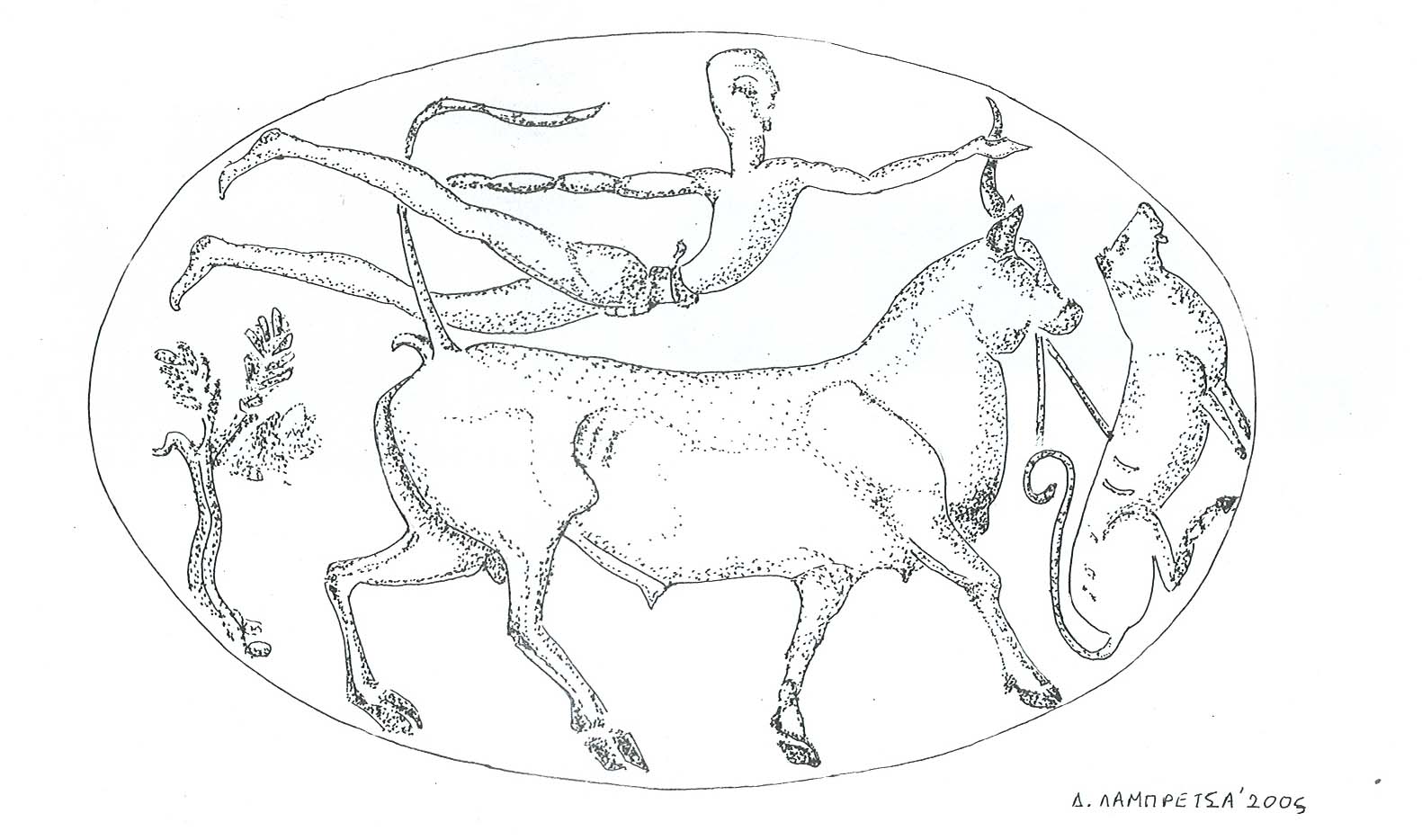

Gold signet ring from the Acropolis (Ring of Theseus) with a representation of bull leaping.

National Archaeological Museum

Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities, inv. no P 19356

Origin: Acropolis of Athens (allegedly)

Dimensions: bezel diameter: 1.8-2.7 cm, ring diameter: 2 cm.

Dating: 1500-1400 BC

Exhibition space: Gallery 3, Showcase 1

The precious gold signet ring was handed over to the National Archaeological Museum in 2004. According to his last owner, it was accidentally found in the 1950s in the area of Anafiotika, where the rubble from the extension of the old Acropolis Museum was carelessly rejected. If the testimony is true, then we have before us the personal object of a Mycenaean noble. Depicted on the ring’s sealing surface is a scene of bull-leaping, a special public spectacle. In the center of the show, an acrobat jumps over a bull. The central figures are framed by a sitting lion and a tree. The depiction of the bull-leaping, – the par excellence Minoan palatial ritual and sport – on a prestigious object of the Athenian king (or his consort) seals the succession of an older and well-known symbol of distinction by the new rulers of the prehistoric Aegean: the Mycenaeans.

Moreover, the signet ring, as well as a contemporary fragment of a stone vase with the same subject, also from the Acropolis, probably refer to the myth of the first king-settler, Theseus, who subdued the fierce power of the Minotaur and the mighty king Minos of Crete and freed Athens once and for all from the cruel blood tax it had been paying until then.

The inhabitants of the prehistoric Aegean seem to have loved public spectacles. The risky sport of jumping over a bull must have been particularly popular on the island of princes, lilies and palaces, as evidenced by its frequent depiction in Minoan works of art. The impressive spectacle seems to have had a deep ceremonial significance and was connected with the religious beliefs and traditions of Crete. Nevertheless, it would also have an entertaining character. The confrontation in public of a man with a wild animal would have been a source of mass anguish, adrenaline and wild joy in the event of victory. Finally, it is not at all certain that the sport survived in the Mycenaean world, judging by its rare appearance in iconography and if one takes into account the peculiar realism of Mycenaean society, which gradually got rid of all its Minoan loans.

Dr Kostas Paschalides

Bibliography:

Iakovidis S., The Mycenaean Acropolis of Athens, Athens 2006.

Marinatos N., Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image and Symbol, University of South Carolina Press 1993, 218-220.

Mountjoy P. A., Mycenaean Athens, Jonsered 1995.

Papazoglou-Manioudaki L., “The gold ring said to be from the Acropolis of Athens”, in Daniilidou, D. (ed.), ΔΩΡΟΝ Τιμητικός τόμος για τον καθηγητή Σπύρο Ιακωβίδη, Athens 2009, 581-598.

Sakellarakis J. A., “Mycenaean stone vases”, SMEA 17 (1976), 184 pl. 12, 32.

Xenaki-Sakellariou A., “Les bagues-cachets créto-mycéniennes: art et fonction”, in Pini I., Poursat J.-C., Sceaux Minoens et Mycéniens (CMS Beih. 5), Berlin 1995, 313-329.

Younger J. G., “Bronze Age representations of Aegean bull-games, III”, in Laffineur R., Niemeier W.-D. (ed.), POLITEIA Society and state in the Aegean Bronze Age, Liège 1995, 507-545.

Website references:

https://www.namuseum.gr/hidden_museum/to-dachtylidi-toy-thisea/

https://www.namuseum.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Unseen_ring.pdf