Exhibit of the month

The Greeks united fill the stadiums

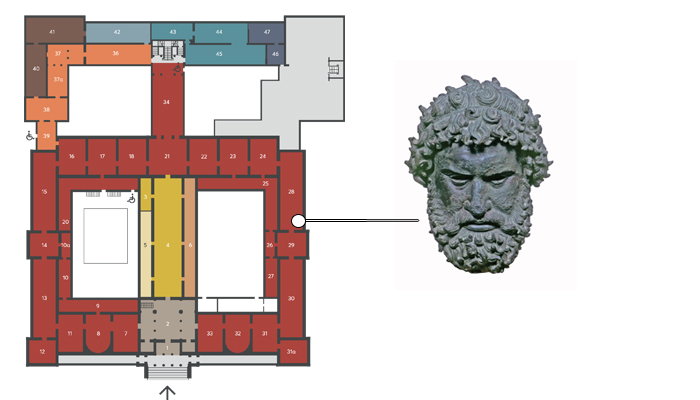

Bronze portrait head from a boxer’s statue

National Archaeological Museum,

Collection of Metalwork, inv. no. X 6439

Provenance: Sanctuary of Olympia

Dimensions: Height 28 cm.

Date: 330-320 BC

Display location: Room 28

The life-sized head belonged to the statue of a boxer who won at the Olympic Games. It was discovered in the sacred grove of Olympia (Altis), where the panhellenic sanctuary of Zeus was located and the Ancient Olympics were held. Round the head he wears a wreath of wild olive branch, the so-called kotinos, awarded to Olympic victors, which preserves only the stem tied at the back and some stalks for the fallen leaves. The dense hair, the beard made of uncombed small locks of hair and the thick moustache are all enlivened with engraved details. The small eyes had inset pupils made from other material. The flabby skin together with the wrinkles on the forehead and the outer corners of the eyes testify to an advanced age, while the deformed nose and the swelling of the ears, cheekbones and forehead muscles reveal long-term boxing matches and hours of hard training. This realistically rendered figure of the late 4th c. BC is most probably the portrait of the famous boxer Satyros from Elis. Pausanias, the Greek traveler of the 2nd century AD, mentions (VI,4,5) that as early as the 6th c. BC in Olympia were erected statues in honor of the Olympic victors. Among them he saw the statue of Satyros, work of the Athenian bronze-sculptor Silanion[1]. Athletes like Satyrοs were considered among the most influential individuals in society and received supreme honors, privileges and eternal glory.

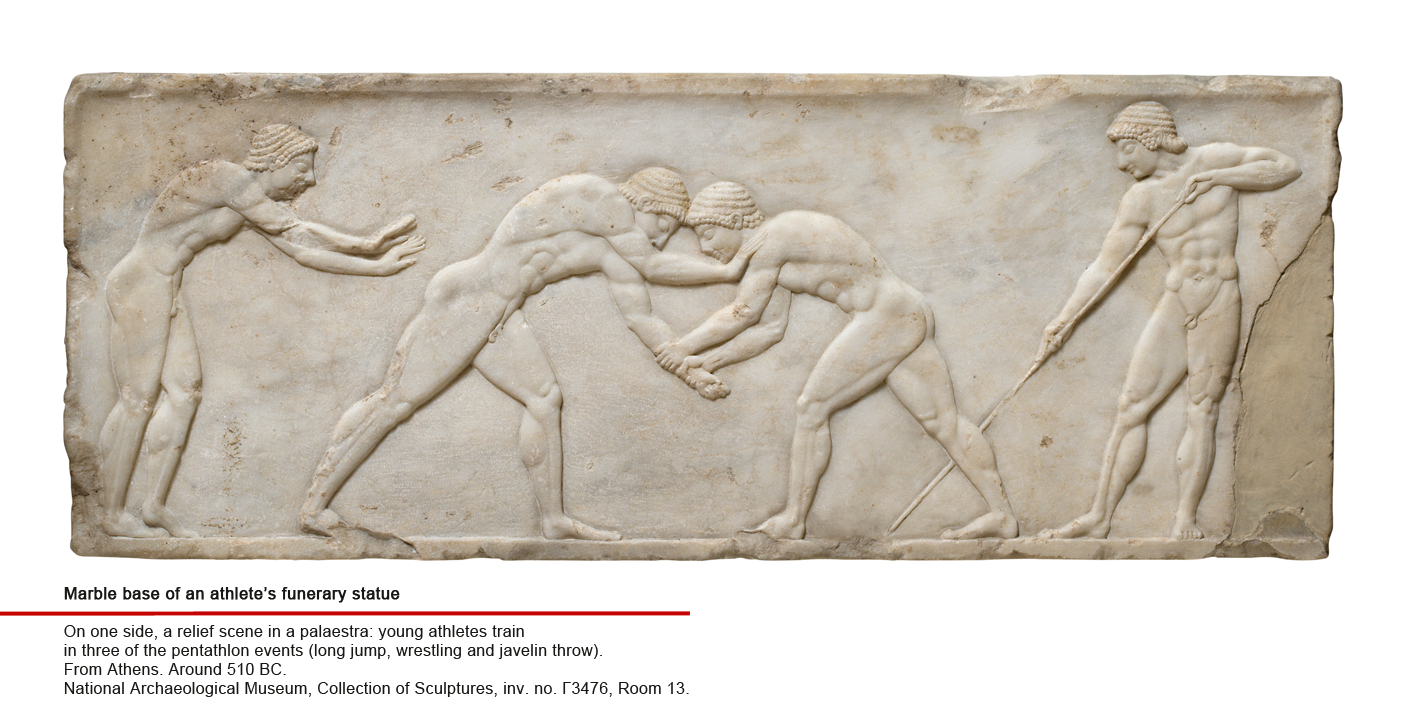

Satyros had been twice a winner in Olympia, but he had also achieved many victories in other two Panhellenic Games of antiquity, specifically in the Nemean and the Pythian which were held in the sanctuary of Zeus in Nemea and Apollo in Delphi respectively. The Isthmian Games held in the sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia, close to Corinth, were the last of the four sets of Panhellenic Games, during which a crowd of athletes and spectators gathered from all over the known Greek world at that time. The Olympics and the Pythian Games were held every four years, the Nemean and the Isthmian every two years, arranged in such a way that the Greeks attended at least one set of Panhellenic Games every year[2]. They have been called “Crown Games”, because the winning prize was a simple wreath with leaves of wild olive at Olympia, laurel at Delphi, wild celery at Nemea and pine at Isthmia. Panhellenic Games were closely connected with the religious life of the ancient Greeks; they were held at prominent sacred centers and in the context of panhellenic celebrations aiming to honor the gods[3]. It was an opportunity for all Greeks to gather together, a fact that contributed to the strengthening of what united them, the softening of what separated them, the stimulation of the national consciousness and faith in common origins. Above all, the Panhellenic Games were a grand celebration of sports. Spectators filled the stadiums to watch, admire and cheer on the athletes competing in the pentathlon (“five events” consisting of running, wrestling, long jump, javelin throw and discus throw), boxing, pankration (a combination of wrestling with boxing), horse and chariot races, at a time when athletics were intertwined with the ancient Greeks, while the competitive ideal is reflected in all the aspects of their life.

[1] Silanion specialized in statues of humans and portraits. He was active in the late 4th c. BC, a time stamped by the work of insurmountable artists, such as Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos.

[2] The Antikythera Mechanism, retrieved from the wreck off the Antikythera island and recognized as the oldest surviving multi-complex astronomical and calendrical portable mechanical computer in the world, is equipped with the so-called Games dial. Ιt displays the 4-year Olympiad cycle and bears the inscriptions ISTHMIA, OLYMPIA, NEMEA, PYTHIA, also NAA (=NAIA) which were games held at Dodoni in honor of Zeus, and probably ΑΛΙΕΙΑ (“Halieia”) games held at Rhodes in the Hellenistic period in honor of the Sun (halios in the doric dialect). The Games dial is part of fragment B of the Antikythera Mechanism (EAM, inv. no. X 15087) visible only in CT slice. Its function had been ascertained in the course of the examination of all the surviving fragments of the Mechanism with modern technological methods by the Antikythera Mechanism Research Team (2005 onwards).

[3] The prominence of the four specific sanctuaries is linked to their geographical location, to their political power or to that of the city-state that controlled them, but mainly to ancient traditions and the beginning of the establishment of local Games there, initially in honor of a local hero or a prominent dead human.

Alexandra Chatzipanagiotou

Bibliography:

Dafas, K., Greek Large-scale Bronze Statuary. The Late Archaic and Classical Periods, London 2019, 134-136, pl. 157-159.

Kaltsas, N., Sculpture in the National Archaeological Museum. Athens, Los Angeles 2002, 248, cat. no. 517.

Kaltsas, N. (ed.), Agon, National Archaeological Museum, 15 July – 31 October 2004, Exhibition catalogue, Athens 2004, 218-219, cat. no. 108 (Μ. Zapheiropoulou).

Stambolides, Ν. – Τasoulas, G. (ed.), Ολυμπιονίκες της Αρχαιότητας, Αthens 2004, 111.

Vorster, Chr., “Die Porträts des 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr.” in Bol, B.C.(Hrsg.), Die Geschichte der Antike Bildhauerkunst II, Klassische Plastik, Mainz am Rhein 2004, 397-399, 544, fig. 369.

Selected bibliography for the Panhellenic Games:

Evjen, H.D., Ancient Greek athletics: an overview, Athens 2018.

Kaltsas, N. (ed.), Agon, National Archaeological Museum, 15 July – 31 October 2004, Exhibition catalogue, Athens 2004.

Miller, S.G., Ancient Greek athletics, New Haven/London 2004.

Spathari, Ε., Το Ολυμπιακό Πνεύμα, Athens 2004.

Selected bibliography for the Antikythera Mechanism’s Game’s Dial:

Kaltsas, N. – Vlachogianni, El. – Bouyia, P. (eds.), The Antikythera Shipwreck, the ship, the treasures, the mechanism, April 2012 – April 2013, National Archaeological Museum, Athens 2012, 247, 266.

Jones, Α., A Portable Cosmos. Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder of the Ancient World, New York 2017, 50, 87-94.